Chloe Bensahel

Name: Chloe Bensahel

Studio location: Washington, DC / Paris, France

Website / social links: chloebensahel.com, @chloebensahel

Loom type or tool preference: Tapestry loom (low warp)

Years weaving: 5 years

Fiber inclination: hand-spun paper thread, linen, conductive thread

Current favorite weaving book: I’ve been doing tons of research lately on historical connections between craft and engineering. The Fabric of Interface by Stephen Monteiro retraces the history of contemporary digital devices and their roots in textile labor and culture. It’s mind blowing.

1. How did you discover weaving and was what your greatest resource as a beginner?

As an undergrad at Parsons, I was in a brand new program created in 2008 called Integrated Design that looked at design as a system, with special attention paid to the materiality of objects. Laura Sansone, who runs the New York Textile Lab taught us everything from weaving, to the history of plants and their connections to historical systems. I started experimenting on a frame loom and researching global traditions. I was hooked from that point on.As a beginner, my greatest resource was probably travel – I looked for teachers everywhere: Japan, Australia, France. I found grants or worked for room and board. I like learning, plus I now know how to farm cotton and indigo!

2. How do you define your practice – do you consider yourself an artist / craftsperson / weaver / designer / general creative or a combination of those? Is this definition important to you?

Artist/craftsperson and I would add researcher. The last one is important because I’m sometimes disappointed by the representation of textiles as accessory. Textiles, in their fabrication or appearance, have historically had a profound impact on our economic systems and on different forms of innovation. I find working with research institutions or archives really stimulating as a craftsperson.

3. Describe your first experience with weaving.

Oh dear. It was a mess, and not at all a peaceful experience. I had this old frame and just put threads on it. They were unevenly spaced apart. The result didn’t even really hold up – it came undone. It was really hard! It left a sour taste in my mouth for a couple of years – I tried everything else: knitting, embroidery, felting.

I finally came back to it a couple of years ago when I had observed other people weaving for long enough. That’s actually how apprentices learn in Japan – they don’t even touch the material until a year in because they need to learn how to look.

4. What is your creative process, from the initial idea to the finished piece? Are there specific weave structures, looms, or fibers that are important to your process?

I usually start with a word or a phrase – language dictates the form of the work. From the word or the phrase I’ll see what medium is best – performance, weaving, or installation? Then I’ll select the materials according to texture, then color (or lack thereof in my case – I’m pretty shy or I let the writing dictate the color.) Then I make it and decide on a presentation. If it’s a performance there are other spheres to work with like sound and space. Sometimes this process can take years if I don’t know how to make the work. For “Words Weave Worlds” for example, I had wanted to make words that speak for years without the means or access to expertise to do it. Right now, I’m working exclusively with tapestry looms, at the French National Tapestry Workshop (Mobilier National) and experimenting more with conductive threads.

5. Does your work have a conceptual purpose or greater meaning? If so, do you center your making around these concepts?

Yes, I came to textiles and weaving for their materiality and relationship to the body – more specifically the culturally mixed body. Most cultures have some type of textile tradition in one form or another, and cloth is very tied to how communities pass on and communicate their stories. I am the last of three generations of immigrants from various countries, which means that my relationship to language as a cultural signifier is somewhat fluid. Weaving and its many threads, the pliability of the material, is something I feel close to. I weave soft language, language that fades, language that is decimated or reconstructed, because that’s my relationship to it – it’s a constant performance.

6. What is your favorite part of the weaving process and why? What’s your least favorite?

I’ll start with my least favorite – warping because in tapestry it disappears anyway.My favorite part is that moment when you have your pattern and everything you need to weave. You can just drop into your hands and body. Generally I’ll put on some podcast or techno, and just let my body take over. I think it’s when I most feel like myself.

7. Do you sell your work or make a living from weaving? If so, what does that look like and how has that affected your studio practice?

I sell my work a bit, but I also apply for many grants. There are a lot of rejections, but every once in a while… I also do some translation on the side (French-English.) For me as a weaver, time is the most difficult resource to manage, so I try to plan as much as I can.

8. Where do you find inspiration?

History is a big one. Old textiles, stories, songs, etc. Once I was reading an archive from the Holocaust museum on the history of stripes, and learned a mistranslation led to stripes being attributed to prisoners. Immediately, I knew that it had to be a work, which led to “Veste Quae Ex Dobus Texta Est Non Indueris” (the text in question). Other times, it’s a technique. At Le Mobilier National, for example, I heard of slits in tapestries left open intentionally to create shadows, which led me to create tapestries with exposed slits so that shadows give hints of words (“Words Weave Worlds”).

9. What other creatives do you admire – weavers, artists, entrepreneurs – and why?

Sheila Hicks probably had the biggest impact on my life track as a weaver. I was still working as a designer in fashion and had the chance to meet her in 2014. She encouraged me to do my work and introduced me to friends of hers in Japan. When you’re just trying to find your place and someone that important in the field tells you to go for it – you follow their instructions very carefully.

I love Magdalena Abakanowicz for her visceral representations of textiles, and Sophie Calle for how intimate her work is. Creative technologists like Ivan Poupyrev who created Google Jacquard and Jonathan Tanant at Google Arts and Culture – those guys make magic.

10. If you could no longer weave, what would you do instead?

I would probably be a historian or an anthropologist. I like the quest.

Do you have any upcoming exhibits, talks, or events the community should know about?

Projects are a bit frozen but I’m starting a Smithsonian Research Residency next year so look out for that!

works include:

Words Weave Worlds, 2019, collaboration with Google Arts and Culture, Google Jacquard, and Le Mobilier National.

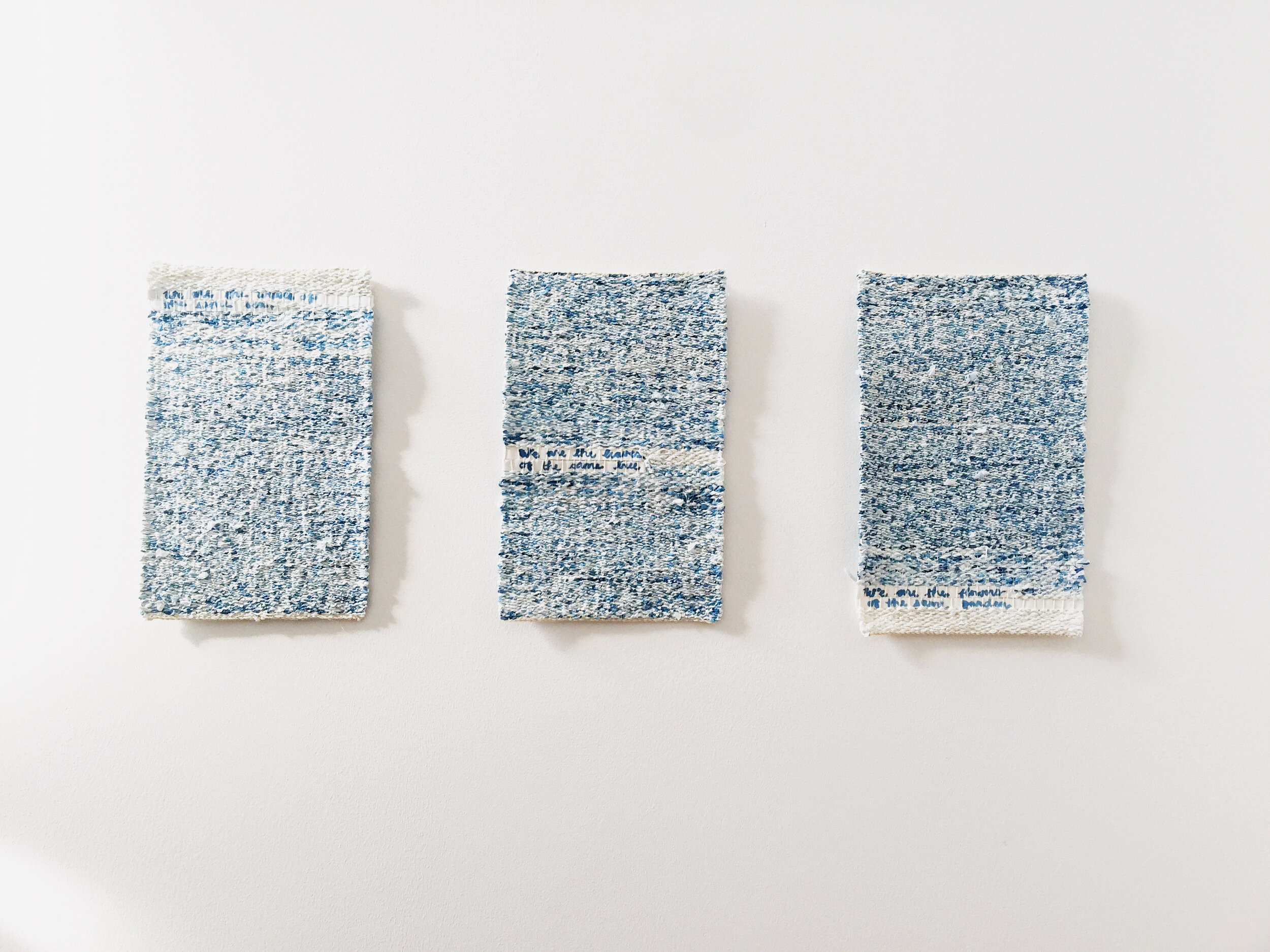

"We Are" series, 2020, based on poems sent between nations during covid-19 (hand-spun paper thread)

Veste Quae Ex, Dobus Texta Est, Non Indueris, 2018, installation made from deconstructed striped shirts

"Foreign Lands," 2020, based on poems sent between nations during covid-19 (hand-spun paper thread)